Sweet Bean Paste by Dorian Sukegawa. Translated into English by Alison Watts

Publication date: November 14, 2017 (English Translation)

First published February 2013

Japanese Title “あん” (An)

I really enjoyed Sweet Bean Paste. It was a finely balanced slice-of-life story about the paths people take and the way they connect with each other, and a story about dealing with your past. It unfolds gradually and naturally. It’s a story with a message, which a few critics feel was a bit heavy handed. In hindsight I can see what they mean, but it didn’t bother me at all during reading.

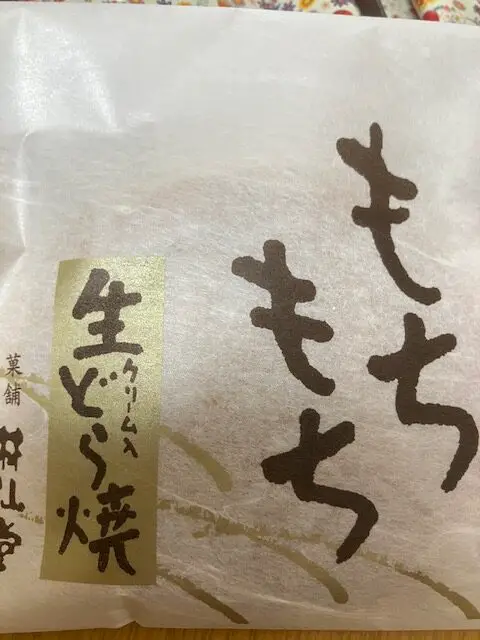

Sentaro is living a life with no direction. His dreams of being a writer have fallen away. He spent a few years in prison which has alienated him from his family. Having been bailed out of financial problems means he’s obligated to work at a small, not particularly good, dorayaki shop making pancakes filled with sweet bean paste. Into this job he puts in as little effort as possible.

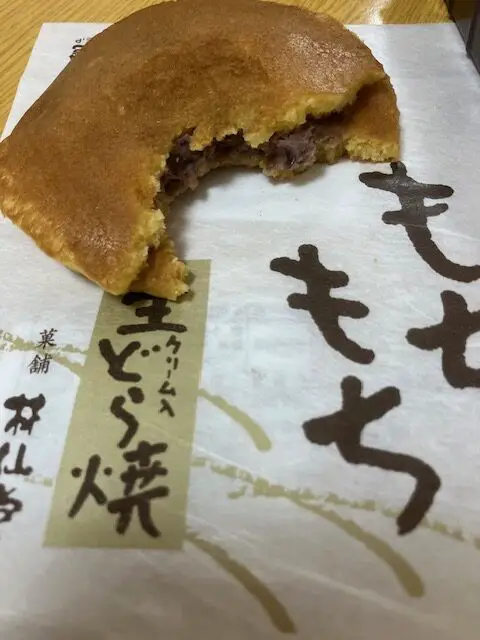

One day Sentaro notices the elderly Tokue watching him from across the street. She approaches the shop and tells him she’s interested in working there. She’s in her 70s, her hands are gnarled and her face has a strange look. He doubts that she will be able to physically do the job. But, after saying she’s willing to work for half wages, and eventually the paltry sum of 200 yen per hour (about 2 U.S. dollars), Sentaro relents and hires her to make the sweet bean paste in the back of the store, while he fries the pancakes and serves the customers. Tokue’s bean paste is delicious. As they work together the fortunes of the dorayaki shop start to improve. Sentaro imagines paying off his debt faster and finally life has the spark that it has been missing.

But Tokue’s past is also dark. Growing social pressure, and fear, means that her secret is exposed and she must leave the shop. But not soon enough to save the store from financial catastrophe.

It’s a simple read. After the first few pages most people will guess where it is heading. A troubled younger person meets a mentor figure that their initial reaction is to try to stay away from. Eventually their relationship develops and they form an unlikely friendship which ultimately transforms them.

The story is incredibly sad. Bittersweet. Almost like the resulting dorayaki. Although I guess that’s more of a salty sweet. It deals with societal prejudice and isolation. But it’s ultimately triumphant, celebrating the little things, the things that are enjoyed with the senses: like food and sweets.

Dorayaki is a Japanese sweet consisting of two small pancakes wrapped around the filling of sweet azuki bean paste. In Japanese “dora” means “gong”, and because of the shape of the pancakes, this is probably where the sweet got its name.

A Few Negatives

A strong theme of the novel is the stigmatism of a certain social group. The theme could have been explored in a more rounded way. Through Sentaro’s viewpoint we discover the story of the group that is discriminated against. Sentaro is put in an awkward situation, and his character embodies the conscience of the story, as he is asked to fire Tokue when he knows that she is cured and no risk to customers.

Representing the other side of the argument is the owner of the dorayaki shop who wants Tokue fired. She comes across as hard-nosed, but she’s certainly no villain. She has a valid point that the stigma surrounding the disease might be bad for business, and ultimately she is proved to be correct. While, the character of the owner was handled subtly enough that she didn’t come across as a type, merely a villain that the narrative wants us to dislike, I did feel that if the story had given her opinion a little more time on the page the issue wouldn’t have felt as one-sided as it did to some critics.

It’s too cloyingly sentimental for my taste and prone to consciousness-raising infodumps.

Cameron Woodhead – Sydney Morning Herald

Sweet Bean Paste is, rather too obviously, a message-novel, meant both to educate and, of course, to display the wonderful human spirit. Durian makes his case for human dignity, and for everyone being allowed to contribute to, and as such be part of, society — as Tokue has been so eager to do. And he makes it fairly blatantly …..

M. A. Orthofer – https://www.complete-review.com/reviews/japannew/durians.htm

I also feel that there are parts of the novel that are too “on the nose”. There is a subplot of an injured bird that a high school girl finds and nurses back to health, the bird eventually ends up in Tokue’s care. Tokue, who has herself been ‘imprisoned’ unjustly, eventually lets the bird free without the owner’s permission because she can’t bear to see it kept apart from the world. Tokue explains her decision in a letter.

There is a scene in the story, after Sentaro leaves the shop and he is depressed, it all seems very distant. I think we’re supposed to believe that he really is contemplating suicide, but I just don’t feel it. Translation? Culture?

In fact this distance seems to be counterpoint to the immediacy of when the narrative is dealing with food.

There is A Lot to Like

Overall, the reception of Sweet Bean Paste has been overwhelmingly positive. There are a number of reasons that I enjoyed the novel. Firstly, the focus on marginalised characters seems to be a big topic in modern Japanese fiction, which is great. I’ve certainly never come across a main character in Japanese literature who has been in prison. And I appreciate the fact that him being an ex con is not lingered upon, it’s not a huge part of the story, just something in his past that’s contributed to where he is today. I’ve recently read Convenience Store Woman which similarly focuses sharply on a marginalised member of society.

Before the secrets of the story are exposed there is a great period of the book where Sentaro and Tokue are getting to know each other. At times it has the feel of a mismatched buddy comedy. Early on Sentaro is reluctantly putting up with Tokue’s eccentricities, until step by step he begins to see her value.

‘I had one of your dorayaki the other day. The pancake wasn’t too bad, I thought, but the bean paste, well…’

“Sweet Bean Paste” by Dorian Sukegawa. p. 11. Translated by Alison Watts.

‘The bean paste?’

‘Yes. I couldn’t tell anything about the feelings of the person who made it.’

‘You couldn’t? That’s strange.’ Sentaro made a face as if to show how regrettable that was, though he knew full well his bean paste could reveal no such thing.

‘It was sort of…lacking.’

In this section I love how Sentaro deadpans his reaction. It seems to me that he is caught between thinking that Tokue is a complete lunatic, and wondering if there’s something about bean paste making that he’s totally missing.

‘It’s all very complicated,’ he blurted out.

“Sweet Bean Paste” by Dorian Sukegawa. p. 27. Translated by Alison Watts.

‘It’s just good hospitality,’ Tokue countered.

‘For the customers?’

‘No. The beans.’

‘The beans?’

‘Because they came all the way from Canada. For us.

The immediacy of the writing, especially to do with food. As well as the way food can evoke memory and feeling. We didn’t hear much about Sentaro’s mother during the novel, all we really know is that she died while he was in prison, which made the following passage really stand out.

Memories of his mother…She was softly spoken but troubled by anxieties beneath the surface that she could not conceal. Then there were the loud disputes with his father, and arguments with relatives that made her cry and scream. As a child Sentaro had been frightened of these outbursts, that’s why he’d wished there could always be cake on the table. Because his mother had a sweet tooth, and whenever they had sweet things that she liked, such as manju buns or cake, she would be in a good mood and he could also feel at peace. He loved his mother when she smiled and said to him, ‘Mm, isn’t this delicious, Sen?’

“Sweet Bean Paste” by Dorian Sukegawa. p. 14. Translated by Alison Watts.

I recommend this book to anyone who likes stories about food, especially sweets. The descriptions of the food and the cooking process are beautiful, and quirky. If you’re in to Japanese literature at all and you’d like to read a “quiet” Japanese story. The relationships in the story are formed slowly and quietly but the implications of the relationships are harsh. Though the reading of the novel is enjoyable it does take a hard look at some aspects of Japanese culture. The community is painted as not very accepting and quick to stigmatise a group even in the face of scientific evidence.

Spoilers Follow

Tokue has lived almost her whole life in a sanatorium for leprosy. Despite being asymptomatic and ‘cured’ for several decades, Tokue’s appearance still bears traces of the disease and, sadly, fear and misunderstanding mean the community talks and customers slowly stop visiting the dorayaki shop. It’s devastatingly sad. The people inside the sanatorium only want to get back to their families. When their eventual release comes they have no families left, and they discover that society doesn’t want them.

Leprosy Repeal in Japan – Comparison with Other Countries

I didn’t know anything about leprosy and leprosy segregation laws until reading this novel. Of course, that led me to wonder how late the Japanese government was at repealing the leprosy laws in comparison to other countries. The feeling of the story is that it is unreasonably late.

It’s difficult to find dates as definite as the Japanese Repeal Law in 1996. Different countries, states, and institutions closed at different times. But in the U.S. “Hansen’s disease officially becomes an outpatient diagnosis in 1981.”

https://www.hrsa.gov/hansens-disease/history

And there was a U.S. leper colony on the Hawaiian Islands, which “patients have been free to leave since 1969.”

https://www.history.com/news/leprosy-colonies-us-quarantine#

In Australia it was as early as 1958.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fantome_Island_Lock_Hospital_and_Lazaret_Sites#

So, the 1996 Leprosy Repeal Law was remarkably late in Japan, and a long time coming. It makes the story of what the people suffered in the sanatoriums in Japan even more devastating and the novel rightfully points out a social injustice. Especially if the survivors of the sanitariums are still discriminated against today.